Kangaroo hunting in Wake in Fright

Death, debauchery and survival in two early ’70s film classics

I’ve recently acquired an interest in the so-called Aussie New Wave cinema of the 1970s and 80s. Although encompassing a range of genres and often overlapping with what is known as Ozploitation, the period really identifies a period of resurgent confidence and productivity in Australian cinema rather than any kind of aesthetic stance. That said, a number of the stronger works of the ‘Wave’ seem to capitalize on the country’s geographical peculiarities with strange and often sinister results. Notable filmmakers who came of age during the period include Peter Weir and Philip Noyce, who went on to enjoy successful Hollywood careers.

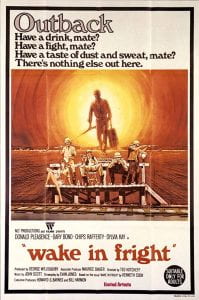

One early example of Aussie New Wave cinema was the Ted Kotcheff-directed Wake in Fright, released the same year as Walkabout (1971). As with Nic Roeg’s classic, its authentically Aussie credentials would be questioned in part due to its foreign director (Kotcheff is Canadian while Roeg is British) and it fared badly at the box office down under. Both films are unsettling and unflattering portrayals of contemporaneous Australian life and are strikingly unromanticized visions of the antipodean wilderness (Wake in Fright was released under the moniker Outback in Europe, where it fared much better). Not unlike Walkabout, Wake in Fright takes place in a hinterland Australia where the veneer of civilization rapidly disappears.

One early example of Aussie New Wave cinema was the Ted Kotcheff-directed Wake in Fright, released the same year as Walkabout (1971). As with Nic Roeg’s classic, its authentically Aussie credentials would be questioned in part due to its foreign director (Kotcheff is Canadian while Roeg is British) and it fared badly at the box office down under. Both films are unsettling and unflattering portrayals of contemporaneous Australian life and are strikingly unromanticized visions of the antipodean wilderness (Wake in Fright was released under the moniker Outback in Europe, where it fared much better). Not unlike Walkabout, Wake in Fright takes place in a hinterland Australia where the veneer of civilization rapidly disappears.

I watched Wake in Fright for the first time shortly after rewatching John Boorman’s Deliverance, released a year later (1972). The films seemed companion pieces in a sense: both feature supercillious metropolitan types who find themselves in seemingly lawless backwaters. In Deliverance, of course, a canoing trip turns nightmare as its city slicker protagonists find themselves the target of unwelcome attention from psychotic hillbillies. An ordeal of death, rape and murder ensues, leaving one of its survivors Ed (played by Jon Voigt) uncertain he will be the same person ever again, the bloodthirsty past threatening to resurface like the bodies of his rural antagonists.

Deliverance is an unforgettable work of horror, even if it was arguably meant to be more than that. Roger Ebert was surprisingly scathing, complaining about how the film’s consideration of “civilized men in a confrontation with the wilderness” is wasted on “exploitative sensationalism”. I would say that is a bit harsh, but it may be better to approach the film as a work of horror than some kind of meditation on civilisation (albeit one that has probably led to some lasting prejudices towards rural Americans).

Deliverance is an unforgettable work of horror, even if it was arguably meant to be more than that. Roger Ebert was surprisingly scathing, complaining about how the film’s consideration of “civilized men in a confrontation with the wilderness” is wasted on “exploitative sensationalism”. I would say that is a bit harsh, but it may be better to approach the film as a work of horror than some kind of meditation on civilisation (albeit one that has probably led to some lasting prejudices towards rural Americans).

Wake in Fright is also something of a journey into a heart of darkness and was actually billed as a horror film. Parallels with Deliverance abound, but instead of lush Deep South forest, we find ourselves in the relentless heat and emptiness of the Australian outback. But (to this viewer at least) the hero John Grant’s (Gary Bond) journey into the underbelly of Australian society is more symbolic than that of Deliverance, taking in a whole gamet of unhealthy Aussie vices.

Stopping over in the mining town of Bundanyabba (known colloquially as “The Yabba”), a cultural and culinary void where the locals are aggressively, even oppressively hospitable, a pervasive fear that he will never be able to leave quickly engulfs him. This is compounded not only by his own failed physical attempts to depart, but also by the sinister figure of Clarence “Doc” Tydon, with whom he briefly lodges. A highly educated former medical practitioner, the Doc offers Grant a glimpse of what he could ultimately become if he cedes to the Yabba’s “charms”: vagrancy, drunkenness and perversity.

The “two-up” scene in Wake in Fright

The film just keeps upping the ante: from a disastrous game of “two-up” and all-day drinking binges to savage kangaroo hunts and drunken fighting – John Grant’s descent from urbane young teacher to degenerate is at once phantasmagorical and curiously believable. The hunt scenes in particular are so unhinged that they point forward to dystopian visions of societal collapse like Mad Max, another pivotal Aussie New Wave movie which later spawned its own franchise.

Although its title evokes some kind of Ozploitation slasher flick, it would be fairer to call it a pyschological thriller. Contrary to the survivalist overtones in Boorman’s film, we feel Grant could simply walk away if his will were stronger: his struggle is as much as against himself and his possible surrender to debauchery as against the wild locals he encounters. Incidentally, Ted Kotcheff would go on to direct a more prosaic but nonetheless iconic movie about survival, First Blood (1982), introducing one of Sylvester Stallone’s most memorable heroes, John Rambo.

Both Deliverance and Wake in Fright are ultimately films about men transgressing their own boundaries and even confronting their inner bestiality. Consequently, some today might baulk today at the obsessive focus on the male experience. Yet, despite the occasional appearance of women characters, their broad absence only seems to reinforce the oppressive nature of each film’s vision. Wake in Fright, long considered a “lost classic” until its only surviving print was recovered and rescued from destruction, is easily Deliverance‘s equal and a cinematic landmark.